Paratrooper Circumcision

“Oh, Doc!” was the last thing he said before fainting. It was the last straw, a bizarrely fitting climax to a minor surgical procedure. Minor, that is, if any surgery on the penis can be considered minor.

His temporarily insensate state reinforced a conviction that had been growing in the course of a muggy, late spring afternoon—if I ever get him and me out of this mess, I am never going to do anything so stupid again. This sensible conclusion was followed by an equally certain resolve: I was not, er, cut out to be a surgeon.

I had nobody to blame but myself. Eighteen months earlier I had been a General Medical Officer stationed in the Pentagon. It was an easy, clean, air-conditioned job. Despite the fact that my duties there were responsible for three of the most interesting days of my life as a participant in the JFK funeral, the work was boring, I had to wear the Army equivalent of a banker’s suit, and I hated riding the bus to work. Volunteering to be a military parachutist was my ticket out.

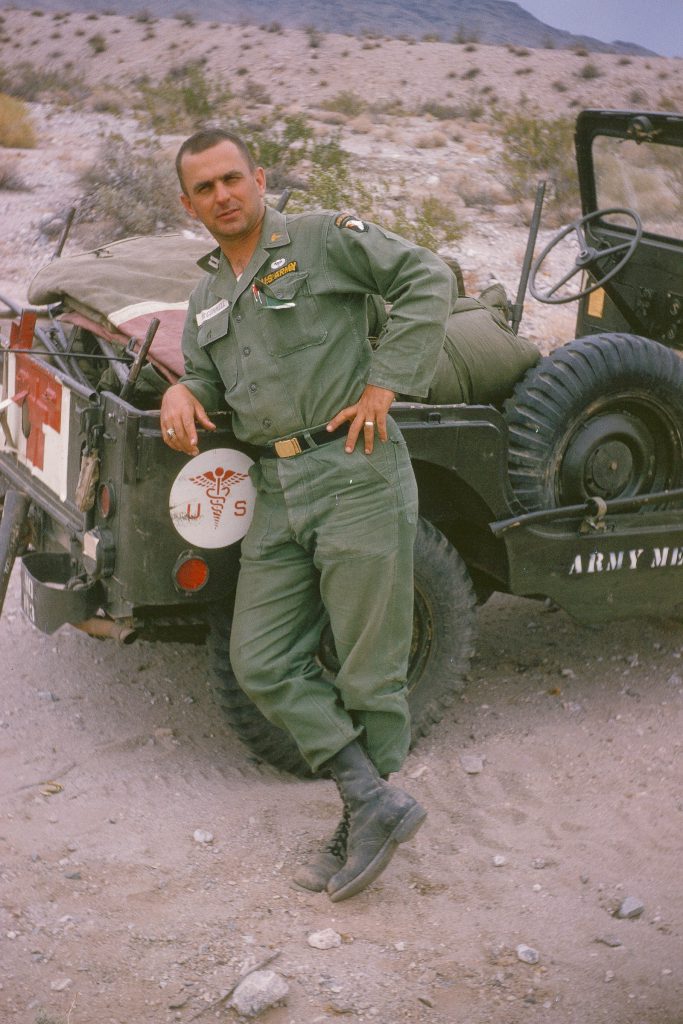

After qualifying as a parachutist, I was assigned as Battalion Surgeon for the 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment of the famed “Screaming Eagles” of the 101st Airborne Division, the intrepid unit that parachuted inland from the Normandy beaches in advance of the main D-Day assault forces, and who later became known as the “Battered Bastards of Bastogne” in the Battle of the Bulge at Christmas 1944.

It was heady stuff. “Battalion Surgeon” had a nice ring to it, despite the fact that my experience with actual surgery was as a medical student, and pretty much limited to holding retractors in an open abdominal incision while real surgeons did the work. The title, however, added to a certain bulletproof feeling, natural to twenty-eight-year-old males, but armor-plated in me after saving lives as an intern and jumping out of perfectly good airplanes and living to tell of it.

I reigned over a kingdom of about a dozen Army medics, most of them not long out of high school. It was wonderful. They were sculpted to conform absolutely to military discipline and drilled in the doctrine of instant obedience to authority. And I was vested with authority—new to a former lowly medical student and intern—which conveyed a feeling of power and mastery that I found pleasing. Very pleasing. Soon I came to believe I was actually masterful and powerful.

My word was law, in certain circumstances practically above that of the commanding officer. Most COs didn’t want to cross “the doc” and mine, a tired veteran of the Korean War, was no exception. We regularly traded favors. On winter bivouacs I would slip him a quart of “medicinal” scotch whiskey and he’d give me extra gasoline for the heater in the aid station tent, where I tenderly cared for the many malingerers who wanted out of the cold.

It was in this state of mind that I agreed to become the team doctor for the 101st Airborne Division football team, where I found the same reverence for “the doc.” Having played football in high school, I got pumped up in anticipation of each game and eager to do my part to ensure victory.

Not being one who would break the ancient and mystical traditions surrounding my calling, I continued the practice of my predecessor shaman in the temple of paratrooper football by administering magical potions. In one ritual I stood at the door and, as the gladiators passed out to battle, popped little white pills into their open gullets like a mother bird tending her chicks. Already fully charged with natural testosterone, they bolted onto the field further stoked by amphetamines. And when violence tore at their bodies and they hobbled to the sideline, I was there for them, ready with crystalline phials of powerful liquids, which I injected to numb the injury or to cloud the pain in a gauzy haze of morphine. “The doc” could do no wrong. It was wonderful.

It was against this background of adulation that our quarterback asked me to circumcise him before his wedding. Ordinarily, this would have been a task for the base hospital urologist, but he was rumored to be alcoholic, so the quarterback asked me. We were brothers at arms, and after all, I had an M.D. degree, I had survived paratrooper school, and a dozen jumps under my belt—I could conquer the world, especially the dull and simple art of circumcision.

He pleaded that he was getting married, and “I know you can do it.” It was all the encouragement I needed. We agreed that it was safer for me to do it in the battalion aid station than to trust his vital equipment to unsteady hands in the urology department at the hospital. After all, how many men can say they have been circumcised by a paratrooper?

I reassured him, and myself, that I’d done a few before. This bordered on fantasy. I’d done a few infant circumcisions, a task so easy that medical students were routinely given the job because it relied on a simple mechanical device that basically pinched off the collar of foreskin and required no stitches. However, as a med student I had seen an adult circumcision in urology clinic and the task was in perfect accord with the mantra we heard as medical students: “See one, do one, teach one.” I’m still waiting for my teaching opportunity.

However, not wanting to trust entirely to experience, I visited the library at the base hospital. Unfortunately, no surgical textbook was on hand, so I settled on an anatomy text to remind myself about the nerves and blood supply. The text clearly demonstrated the bountiful supply of each.

The day of the big event was hot, muggy, and windless. We assembled shortly after noon in a tiny room in the battalion aid station. The patient was sweating profusely and had a big belly, proving the maxim enunciated later by Washington Redskin quarterback Sonny Jergensen, who responded to criticism of his famous beer belly: “I don’t throw the ball with my stomach.”

I gave him a horse-size dose of morphine to ensure docility and dreamy compliance with my instructions, and ordered him to strip naked and lie on his back on the table where his organ would be readily available to my ministrations. I tugged his organ aloft and invited my corpsmen to inspect the anatomy and gave a short lecture on exactly what was to occur.

As the morphine took hold, our victim made nervous jokes with my assistants while I drew up a syringe of Novocaine and capped it with a long needle, the better to reach some of the deeper nerves in the groin, which required accurate injection to deaden the penis. He moaned and squirmed for a while, but after the first few injections, he became quiet again.

Circumcision is simple. Conceptually. The collar of foreskin is pulled forward and two cuts are made, both in line with the middle of the shaft, one on the upper side and one opposite on the lower. This creates two lateral skin flaps, one attached to either side of the penis at the base of the head. These are trimmed away close to the shaft and the resulting circumferential wound is sutured. And, voila, the deed is done!

One of the tricks of this procedure is to use a special long, thin clamp, somewhat like “hog-nose” pliers, to crush the tissue where the initial top and bottom cuts are to be made. This crushing welds the tissue together so that the cuts can be made in the impression left by the clamp. Having crushed the blood vessels and nerves, no bleeding or pain accompanies these initial cuts. However, when I applied the clamp, my patient, whom I’d forgotten remained attached to his penis, groaned loudly, and in his stupor began groping to remove the offending stimulus.

I quickly released the clamp and ordered the corpsmen to tie his arms to the table. After he was suitably bound, I drew up more anesthetic, and injected a full syringe, jabbing here and there at the unseen nerves that had been so easily identifiable in the textbook. By the time I finished, his groin was lumpy and swollen with what amounted to a figurative barrel of Novocaine. Again the clamp produced groans and thrashing. I relaxed the clamp and ordered a chest strap added to the restraints.

By this time I was sweating, nervous and tired, and envious of my patient who, after the offending clamp was removed, lay in peaceful repose. I eyed my work. It did not inspire confidence. His organ issued from a mound of tortured flesh—lumpy, hairy, and oozing blood from the many injection sites, and looked much like he’d gotten in a barroom fight using his organ against an opponent armed with a baseball bat.

But this was no time for second thoughts or half measures, so I applied the clamp with extra vigor and held on until the thrashing stopped.

Next, I made the top and bottom incisions and to my delight the tissue parted cleanly and without further protest or bleeding. But by now a fifteen minute surgery had lasted for the better part of two hours and the morphine was wearing off. Our patient raised his head, straining against his fetters, looked glassily down toward me, and said, “Doc, I changed my mind.”

I dispatched him with more morphine and returned to my labors. My next task was to trim off the flaps by cutting across the base of each one close to the shaft of the penis. It proved far more difficult than anticipated. It was hard to tell where the flap ended and the penis began. I cut a bit here and a bit there, extending them around the edge of the shaft until we got to that most sensitive part on the underside of the shaft near the tip.

Each time I made a small cut the groaning and thrashing began anew. I drew up another syringe of Novocaine and injected more. But to no avail. Every time I tried to trim across the last bit of foreskin he screeched drunken objections.

By this time I was issuing silent promises to heaven that if I was delivered from this situation I would forever keep my promise never to sneer at surgeons as mere mechanics. In this desperate condition, I decided I would deaden the recalcitrant zone by direct injection. I drew yet another syringe of Novocaine and stuck it into the end of his penis. My patient bucked and groaned, and the loose tissue swelled with frightening distortion, its lonely eye now askew with a doubtful glance above a drooping, bloody collar.

I cut again. More thrashing and groaning. Another injection, more cuts, louder groans. By now at wits end, I experienced the truth of a maxim oft repeated in medicine, usually in an emergency room— desperate conditions call for desperate measures.

In a moment of resolve unforgettable at the distance of decades, I said to myself: enough is enough. I grabbed a pair of scissors, pulled forward tightly on the two recalcitrant pieces of tissue, took approximate aim and, in a swoop worthy of an executioner in the court of Henry VIII, I chopped. Screams! Success!

Now to the suturing. I had assumed that the operating room would have an ample supply of sutures. I was right, but the stiff, heavy stuff was for closing shrapnel wounds, not the delicate task at hand. I began to stitch, but the sutures were so stiff they wouldn’t stay tied with an ordinary square knot. So I tied a string of knots in each, a technique more akin to plaiting cornrows in a hair salon than surgical suturing. The result bristled wildly like a rapper’s dreadlocks.

Next came the bandaging. Like most other parts of this ill-advised undertaking, I assumed it would bandage it like anything else. Not so. It was more akin to bandaging a piece of spaghetti. I wrapped this way and that, careful to leave a peephole. None of the successive wraps produced the desired result—the bandage seemed ready to slide away at any moment. I added more and more until I had swathed the thing into a satisfying mound, which was secured to his belly by big strips of white tape.

I roused him from his slumber and asked him to stand and lean against the side of the table. My purpose was to see if the bandage, or his penis, would fall off. He wavered there, grinning foolishly, and then looked down to see what had been wrought. A single drop of blood plopped to the floor between his feet. He looked back up at me with a vacant stare and said, “Oh, Doc,” and fell over in a faint, crushing my work.

We revived him in short order, due no doubt to a favorable response to the most fervent prayers ever issued by a circumciser. I ordered my corpsmen to get him dressed while I went outside to gasp for fresh air. Shortly one of my assistants came to explain that they had an unusual problem: they couldn’t get his penis back in his pants—the thing and its bandage were too large. Our patient, by now hurting and belligerent, wasn’t going to leave the aid station with his organ poking out of his pants.

I gave him a military order that he would damn well do as I instructed. Just when I was about to send him out into the world with his surgery showing, one of my corpsmen suggested we cover him with a poncho. So we pulled up his pants, his bandage protruding, buckled his belt, draped a poncho over him, and sent him home. A few days later I saw him at the base PX, blithely shopping in his poncho.